|

| Lydia Diamond's adaptation for the stage of Toni Morison's first novel. |

Let's talk for a moment about the power of "we all breathe the same air."

Let's let out a sigh of relief for the ability to do this safely, and for those who have ensure that: the scientists and their vaccines, the Biden administration and its focus on distribution and relief.

Let's humble ourselves -- just for a moment! -- in the sweet, anti-American mythology that each of us as individuals does NOT exist in our own pod of self-sufficient, bootstrapped being, but rather is dependent upon everyone before us and around us for who we are.

COVID, a potent symbol of this dependence, remains out there and we still want to reduce and halt community transmission and the variants it allows to develop.

We also want to heal the damage caused by social isolation.

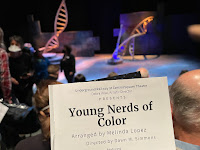

We want to heal the damage to our hearts and souls by two years not experiencing live art together.

|

| A fascinating new play at the Central Square Theater in Cambridge. |

Truly, our crisis in culture -- the arts and humanities -- had been already building steadily in this country for decades pre-pandemic. TV's and even radios beamed entertainment directly to our homes long before the internet, eroding our need to venture into the dangers of the public domain.

Yet the performing arts, unlike TV, are not "just entertainment." When we are live in a room with others, we are not merely on a one-way road, consuming what is transmitted to us; or even in a two-way or multiple player super highway of electronic gaming. We are exchanging breath with the performers and other audience members. We are participating in the creation of that performance and experience.

|

| The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: the privilege of creating one's personal abode as lavish performance-art-to-be- experienced. |

I'll close this one by further referencing my "main woman" of political theory and philosophy, Hannah Arendt. In her essay, "The Crisis in Culture" (1968), Arendt argues that art is political: not in the ways it might speak directly to social justice and change but precisely because it is not a commodity and therefore requires us to gather in the commons where we must accommodate the perspectives of others.

More on the importance of "the commons" -- or the polis -- anon.

#ArtNotEntertainment

#StopConsuming

1. Julia Reinhard Lupton (2014) Hannah Arendt and the Crisis of the Humanities?, Political Theology, 15:4, 287-289, DOI: 10.1179/1462317X14Z.00000000085